In part one of this article, we discussed how joint manipulation could help address local, “arthrogenic” muscle inhibition (AMI.) We then reviewed a relevant study1 our group recently published in the Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics, showing that ankle joint complex (AJC) manipulation has a measurable proximal effect, improving gluteus medius (GMed) activation and strength in subjects with a history of ankle sprain and unilateral hip abductor weakness. In part two, we'll look into the study’s implications for your clinical practice. We'll discuss why:

• Hip abductor deficits are a frequent yet underrecognized finding post-ankle injury.

• The potential consequences of hip abductor inhibition are numerous and progressive.

• These deficits aren’t necessarily correctable by normal means.

• Providers who specialize in manipulation are in a unique position to help the situation.

• Manipulation is a good start, but it is usually not enough on its own.

• Identifying hip abductor inhibition can aid in differentiating the root cause of injuries.

"Providers who specialize in manipulation are in a unique position to help the situation"

I’ve experienced much of this first hand. Until a hip osteoarthritis (OA) diagnosis shut me down, I enjoyed distance running through my early 40s. However, as far back as my 20s (pre-OA), I was plagued with recurring right lateral hip and low back pain (LBP). Chiropractic work would temporarily address the LBP but not really the hip. Core and hip strengthening helped, especially banded “monster walks,” but only to a point. I spent over a decade in a pattern of exacerbation anytime I pushed the mileage or pace.

A light-bulb moment came when I snow-shoed up a steep mountain one winter. As I became fatigued, I could feel my left glutes working overtime, but my right side was conspicuously quiet. Sure enough, later that night, my right hip and LBP returned. Clearly, my right hip abductors weren’t responding to the monster walks as they should. This sparked an investigation that (making a long story short) ultimately led to the culprit—my right ankle.

This ankle had been badly sprained several times as far back as high school, and, despite a good rehab effort (and lack of any remaining ankle symptoms), it was still inhibiting GMed. It wasn’t until I had several effective ankle adjustments that I could feel GMed respond to exercise appropriately. I also realized that my LBP was compensatory; the paraspinals and quadratus lumborum (QL), in GMed’s absence, were working overtime. The ankle-GMed link seemed to connect all the dots, and addressing the ankle finally broke the cycle.

As with any new clinical finding, I immediately started looking for this connection in my patients and found that it was actually quite common, especially among athletes. As I pieced things together over the years, I discovered the following:

Prevalence

Hip abductor weakness2 and deactivation3 are known findings post-ankle injury, although to my knowledge no one has attempted to quantify their prevalence. As a rough indicator, we screened 55 subjects with a history of past inversion sprain to identify 25 that had hip abductor weakness, or 45%. (Most of our subjects were DPT students, who are more likely to be doing hip abductor exercises- meaning a unilateral weakness is conspicuous.) If anywhere near 45% of individuals develop inhibition post-ankle sprain, this could amount to a high occurrence, especially in the athletic population.

"...we learned in this process that we accomplish more with ankle adjusting than we understood. However we were also neglecting more ankle subluxations than we knew."

The Consequences of Hip Abductor Weakness Include:

• LBP, with trigger-point and palpation tenderness over the gluteals, greater trochanter, and paraspinals.4,5 (Empirically, I would add QL, gluteus minimus, and piriformis to the list.)

• Leg pain6

• Adduction and internal rotation in the hip joint during weight bearing while walking7, which is known to increase the Q-angle, cause genu valgum, and displace the patella laterally8 (and create patellofemoral issues).

• Iliotibial band syndrome in distance runners.9

• Patellofemoral OA10

• Lumbar disc disease and hip OA.6

These are the effects of weakness; if anything, inhibition only intensifies things. Many of these effects are a form of synergistic dominance—muscles adjacent to GMed working harder in compensation. Consequently, treating these symptoms (with adjusting, dry needling, foam rolling, etc.) is often only palliative until the underlying inhibition is addressed.

I experienced many of these issues, including ultimately hip OA. While I already had bilateral congenital hip dysplasia, my right hip OA progressed much more rapidly than the left, and I’m convinced that running for many years with an inhibited right GMed accounts for this difference.

Inhibited Muscles Don’t Respond to Exercise Fully or Appropriately

This is essentially how I define AMI to patients. Inhibition decreases muscle activation, and fewer motor units firing means less potential for strength gains. While you will get some response from exercise, the inhibited side tends to chronically lag behind the unaffected side.

The Good News: Adjusting AJC Subluxations Immediately Improves GMed Activation

Clinical tips:

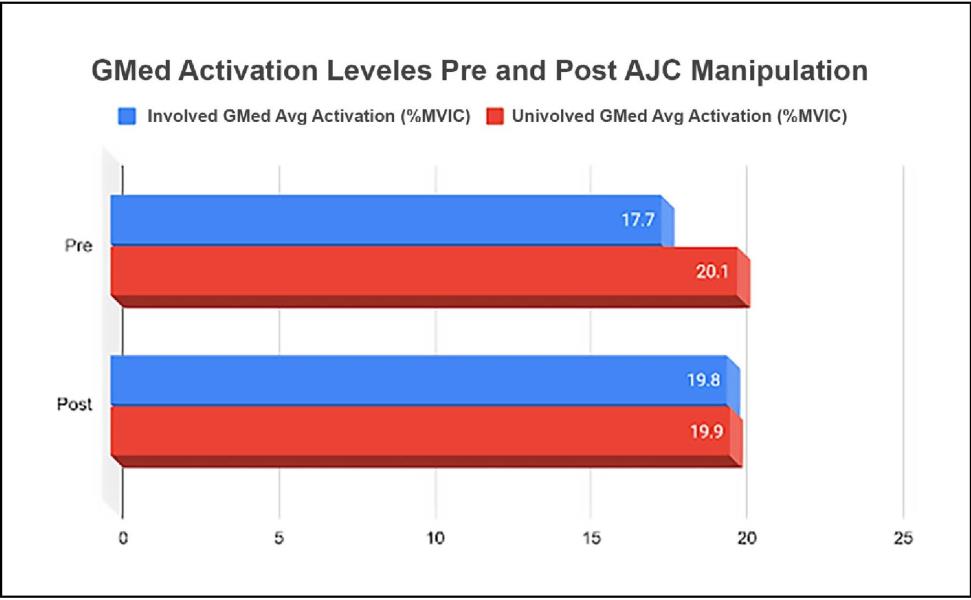

Our study demonstrated a 12.2% average and 9.8% maximum increase in GMed activation immediately following the manipulations, fully abolishing the inhibition:

Increased activation allows for muscles to function appropriately. Within 48 hours, our subjects were already producing more hip abductor force—18.5% average and 14.2% maximum, again up to the same level as the unaffected side. Clinically this should then set the stage for an appropriate response to rehab and treatment efforts.

We see a lot of running injuries at our offices, and as such I’ve performed thousands of AJC manipulations over the years. Having said this, our study revealed an interesting finding of which I had been unaware: while only about half of the subjects required cavitation of the proximal and distal fibular joints, 100% required release of the talocrural and subtalar joints. While the exact mechanisms by which GMed reactivation occurs are not fully clear, apparently these two joints play an important role and warrant close consideration (including their associated soft tissues).

Overall one of the biggest things we learned in this process is that we accomplish more with ankle adjusting than we understood. However, once we routinely started muscle testing the hip abductors, we also realized we were neglecting more ankle subluxations (and consequent GMed inhibition) than we knew.

Ankle mobility and stability deficits must also be addressed.

Rehab-wise, you’ll want to address any ankle balance deficits and intrinsic weaknesses you find. Additionally, patients often needed to “reconnect” to GMed with an isolating exercise. Of the better-validated moves11, the one I’ve found most helpful is a banded, small-amplitude clamshell, with the addition of a thumb directly on the GMed to feel it working (what I call clamshells 'with intent'). When I first started these in my own recovery, I could literally palpate less muscle mass on the affected size.

Together, this mobility, stability, and isolation work will allow for a full resolution of the GMed inhibition and the effects it causes. At this point, more functional, larger-chain hip-abductor maintenance exercises are appropriate, such as monster walks and single-leg squats.

Differential Diagnosis

Another use of manual muscle testing (MMT) is as a quick screen to aid in evaluating the integrity of corresponding joint regions. So, for instance, a weak psoas muscle test often points to joint dysfunction at its origin in the lower thoracic/lumbar region. In the same manner, a weak hip abductor test is your clue to take a closer look at the ankle.

For example, let’s say you are treating a runner with IT band syndrome. If the hip abductors test weak while the other hip muscles (flexors, extensors, and adductors) test strong, it strongly indicates that the problem originates in the ankle. On the other hand, if the psoas or GMax are testing weak, the problem could just as likely be originating from the lumbopelvic region. In our offices, we’ve developed MMT-based algorithms to navigate through such possibilities and uncover root causes as efficiently as possible.

Conclusion

Since learning about and experiencing this phenomenon, I’ve worked with numerous patients who were similarly stuck in a pattern of recurring low back, hip, and knee pain. Many of them had worked with other quality providers and been doing appropriate rehab. Invariably, we find unresolved AJC dysfunction from a past injury that’s still inhibiting GMed. Often the ankle injury was years in the past and not a current issue, and no one had thought to investigate it as a root cause.

On my YouTube channel, I’ve posted some free videos sharing best practices on muscle-testing, ankle-adjusting, soft-tissue work, and rehab—everything you’ll need to find and successfully treat this important clinical phenomenon.

Jamie Raymond, D.C. is a Certified Chiropractic Sports Physician with 20+ years of experience. He specializes in the causes and effects of muscle inhibition as it pertains to musculoskeletal injury, and has developed innovative protocols to help other providers incorporate best practice treatments to tackle their most difficult cases. Check him out on his YouTube channel.

References

1. Lawrence MA, Raymond JT, LookAE, Woodard NM, Schicker CM, Swanson BT. Effects of Tibiofibular and Ankle Joint Manipulation on Hip Strength and Muscle Activation. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2020 Jun;43(5) .406-417'.

2. Friel K, McLean N, Myers C, Caceres M. Ipsilateral hip abductor weakness after inversion ankle sprain. J Athl Train. 2006 Jan-Mar; 41(1): 74-8.

3. DeJongAF, Koldenhoven RM, Hart JM, Hertel J. Gluteus medius dysfunction in females with chronic ankle instability is consistent at different walking speeds. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2020Mar;73:140-148.

4. Cooper NA, Scavo KM, Strickland KJ, Tipayamongkol N, Nicholson JD, Bewyer DC, Sluka KA. Prevalence of glu teus medius weakness in people with chronic low back pain compared to healthy controls. Eur Spine J. 2016 Apr;25(4):125865.

5. Sadler S, Cassidy S, Peterson B, Spink M, Chuter V. Gluteus medius muscle function in people with and without low back pain: a systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2019;20(1):463. Published 2019 Oct 22.

6. Kameda M, Tanimae H. Effectiveness of active soft tissue release and trigger point block for the diagnosis and treatment of low back and leg pain of predominantly gluteus medius origin: a report of 115 cases. J Phys Ther Sci. 2019 Feb;31(2): 141-148.

7. Kim EK. The effect of gluteus medins strengthening on the knee joint function score and pain in meniscal surgery patients. J Phys Ther Sci. 2016;28(10):2751-2753.

8. Earl JE, Schmitz RJ, Arnold BL. Activation of the VMO and VL during dynamic mini-squat exercises with and without isometric hip adduction. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2001 Dec; 11 (6): 381-6.

9. Fredericson M, Cookingham CL, Chaudhari AM, Dowdell BC, Oestreicher N, Sahrmann SA. Hip abductor weakness in distance runners with iliotibial band syndrome. Clin J Sport Med. 2000 Jul; 10(3): 169-75.

10. Sritharan P, Lin YC, Richardson SE, Crossley KM, Birmingham TB, Pandy MG. Musculoskeletal loading in the symptomatic and asymptomatic knees of middle-aged osteoarthritis patients. JOrthop Res. 2017Feb;35(2):321-330.

11. Boren K, Conrey C, Le Coguic J, Paprocki L, Voight M, Robinson TK. Electromyographic analysis of gluteus medius and gluteus maximus during rehabilitation exercises. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2011;6(3):206-223.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue