VERTEBRAL ARTERY DISSECTION is a serious condition that requires prompt diagnosis and treatment. The examination process typically involves a combination of clinical assessment and advanced imaging techniques.

The initial evaluation includes a thorough neurological examination to assess for signs and symptoms of stroke or vertebral artery dissection. These may include:

• Sudden onset of severe headache or neck pain

• Dizziness or vertigo

• Difficulty speaking or swallowing

• Visual disturbances

• Weakness or numbness on one side of the body

• Impaired coordination or balance

Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) is considered the gold standard for diagnosing vertebral artery dissection. This technique combines magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with angiography to provide detailed images of the vertebral arteries. MRA can detect:

• The intramural hematoma, which typically appears as a crescentic shape adjacent to the vessel lumen

• Any luminal abnormalities or occlusions

Other imaging modalities that may be used include:

• Computed Tomography (CT) Angiography: This can provide high-resolution images of the vertebral arteries and is often one of the first tests performed due to its wide availability.

• Conventional Angiography: Although less commonly used now, this invasive procedure can provide real-time images of blood flow and the extent of vessel injury.

• Fat-suppressed MRI: This technique is particularly useful for differentiating small intramural hematomas from surrounding soft tissues.

Time is critical in stroke diagnosis, so rapid assessment and imaging are essential.

Follow-up imaging may be necessary to monitor the progression or resolution

In some cases, a multiparametric approach using T1-weighted imaging, T2-weighted imaging, and time-offlight MRA followed by contrast-enhanced MRA may be beneficial to identify vessel pathology and differentiate hematomas.

It’s important to note that although these examination procedures are crucial for diagnosis, the management and treatment of vertebral artery dissection or stroke should be earned out by specialized medical professionals in a hospital setting.

of the dissection.

The early symptoms of vertebral artery dissection (VAD) can be subtle and varied, but typically include:

• Head and neck pain: This is the most common early symptom, occurring in 50-75% of cases. The pain is usually:

0 Located at the back of the head or in the neck

0 Gradual in onset

0 Either dull, pressure-like, or throbbing in character.

0 Severe and sudden headache, particularly behind one eye.

• Neck pain that may be persistent or worsening.

• Dizziness or vertigo.

• Tinnitus.

• Visual disturbances, such as temporary vision loss or seeing shimmering lights.

• Face pain and numbness.

• Difficulty speaking or swallowing.

• Hoarse voice.

• Loss of taste.

• Hiccups.

• Nausea or vomiting.

It’s important to note that these symptoms can be non-specific and may mimic other conditions. In some cases, VAD may present with only pain as a symptom, making early detection challenging. If any of these symptoms occur suddenly or persistently, especially after neck trauma or manipulation, immediate medical attention should be sought to prevent potential complications such as stroke.

The most common causes of vertebral artery dissection can be categorized into two main groups: spontaneous and traumatic.

Genetic factors: Although only 1-5% of cases have a clear underlying connective tissue disorder, genetic predisposition plays a role.

• These include:

• Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV

• Marfan syndrome

• Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease

• Osteogenesis imperfecta type I

• Vascular abnormalities: Conditions like fibromuscular dysplasia can increase the risk of dissection

Elevated homocysteine levels: Often due to mutations in the MTHFR gene.

Recent respiratory tract infection: This has been identified as a risk factor, with a seasonal peak in fall.

Traumatic causes often involve sudden neck movements or minor injuries, such as:

• Physical activities: Wrestling, yoga, weightlifting, trampoline use, or riding roller coasters.

• Everyday actions: Coughing, sneezing, childbirth, sexual activity, having your hair washed.

• Motor vehicle accidents: Particularly those causing whiplash.

• Prolonged neck positions: Keeping the neck in a hyperextended position for extended periods, such as when painting a ceiling.

It’s important to note that in many cases, vertebral artery dissection occurs without a clear cause, especially in young and middle-aged adults. The combination of intrinsic factors weakening the arterial wall and external triggers often contributes to the occurrence of vertebral artery dissection.

Yes, vertebral artery dissection can indeed be triggered by minor neck movements. This condition can occur due to seemingly innocuous activities and movements, often without significant trauma.

Vertebral artery dissection is more common in younger individuals. It accounts for about 20% of strokes in young people compared to 2.5% in the elderly.

It’s important to note that although these minor movements can trigger dissection, many cases occur without a clear cause. The condition should be considered in patients presenting with sudden onset of headache, neck pain, or neurological symptoms, especially in younger individuals with a recent history of neck movement or minor trauma.

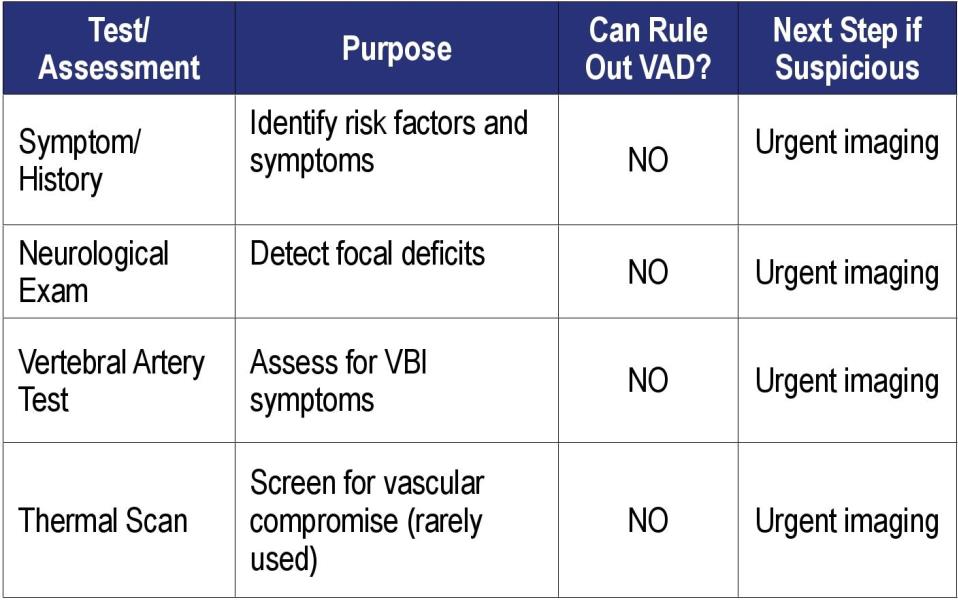

In-Office Tests to Screen for Vertebral Artery Dissection

Key Point:

There is no single in-office test that can definitively rule out vertebral artery dissection (VAD). Diagnosis is ultimately confirmed by advanced imaging (CTA, MRA, or angiography). However, certain in-office assessments can increase suspicion for VAD and guide urgent referral for imaging.

1. Symptom Assessment and History

• Ask about recent trauma.

• Look for sudden-onset, severe, unilateral neck pain or headache, often described as “unlike any pain I have ever experienced before.”

• Inquire about associated neurological symptoms: dizziness, vertigo, double vision, difficulty speaking or swallowing, ataxia, or other brainstem/cerebellar signs.

2. Neurological Examination

A thorough neurological exam is essential to detect focal deficits that might indicate posterior circulation ischemia due to VAD:

• Cranial Nerve Exam: Check for dysarthria, dysphagia, facial numbness, or visual disturbances.

• Cerebellar Testing: Perform Romberg’s test, finger-tonose, rapid alternating movements, and observe for ataxia or dysmetria.

• Motor and Sensory Exam: Assess for limb weakness, sensory loss, or abnormal reflexes.

• Gait Assessment: Look for unsteadiness or ataxic gait?.

3. Vertebral Artery Test (VAT)

The VAT involves positioning the neck in extension and rotation to assess for symptoms of vertebrobasilar insufficiency (VBI)l.

Caution: A negative VAT does not rule out VAD or VBI. It is not sensitive or specific enough to exclude the diagnosis and should not be relied upon for screening.

If the test is positive (provokes symptoms), urgent imaging is indicated.

4. Additional In-Office Observations

Check for differences in skin temperature between sides of the neck (using a thermal scanner), as a 4-degree difference may suggest vascular compromise.

Auscultate for bruits over the carotid and vertebral arteries, though this is rarely diagnostic.

Limitations of In-Office Testing

No in-office test can definitively rule out VAD. The diagnosis is clinical and radiological. In-office tests may raise suspicion but cannot confirm or exclude the diagnosis.

Imaging is mandatory if VAD is suspected: CT angiography (CTA) or magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) are the gold standards for diagnosis.

Conclusion

If vertebral artery dissection is suspected based on history or neurological exam, immediate referral for advanced imaging (CTA or MRA) is required. In-office tests can raise suspicion but cannot rule out VAD. A high index of suspicion and prompt imaging are essential to prevent catastrophic outcomes. And if suspected, do not adjust.

Dr. Gilles LaMarche is a chiropractor, author, professional speaker, and certified personal development/executive coach. Inspired by his own healing journey as a child, he has spent over 40 years promoting health and personal responsibility. Gilles balances a successful career with a fulfilling personal life, deeply committed to helping others achieve their full potential through mind, body, and spirit.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue