The How and Why of Decompression-Traction Patient Positioning

TECHNIQUE

Jay Kennedy

DC

Some 25 years ago, Anthony Delitto et al. published a paper in the journal Physical Therapy regarding extension mobilization as a valid patient subgroup category.1 It was entitled, “Evidence for Use of an Extension-Mobilization Category for Acute Low Back Syndrome.” Extension was determined to have value in helping more accurately create patient classification. The concept of extension was based on work began nearly 40 years earlier in 1956 by Robin McKenzie in his landmark research into disc-derangement syndromes and their tendency to show marked improvement and centralization of pain when repetitive maneuvers (most often extension) were part of the rehabilitation process.2

Though it’s common to call the McKenzie technique an extension-exercise protocol, it’s actually inaccurate. Many various motions, including flexion, lateral bending, and side-gliding, are routinely utilized.3 Since its introduction decades ago, there has been a near entrenchment of the McKenzie method in physical therapy. This has led many to all but abandon the previously standard disc protocols, namely Williams’s exercises (many flexionbased) and axial-traction therapy. As is often the case with treatment trends, eventually the pendulum tends to swing back, at least a little. This is becoming apparent in a renewed acceptance of axial-traction/decompression for many various types of patients.4 A recent survey found more than 50% of physical therapists use traction for herniation with nerve-root compression, often in addition to extension-maneuvers. Chiropractic use is perhaps 30 to 35% of clinics.

Hundreds of research projects have been published since the 1980s involving the McKenzie method. There was also tremendous exposure of this work to the public, not only through McKenzie’s numerous best-selling books but also in mass media publications, on TV programs, and via athletes. As the first decade of the twenty-first century winds down, much research has been published that casts a bit more critical eye toward the protocols. Several systematic reviews are now available that help determine its actual clinical importance. One such review suggests that the benefits of McKenzie maneuvers for the treatment of low back and leg pain are on par with chiropractic, other movement-therapies, and even a personalized education consultation.5 The results, though perhaps statistically significant, often are not clinically meaningful in most long-term outcome studies. Clearly, they do suggest a benefit in the early, acute phase, but that benefit disappears

over subsequent weeks. Other research studies and biomechanical modeling suggest that too aggressive extensionmobilization maneuvers (repetitive back extensions) may prove counterproductive or detrimental to many.6

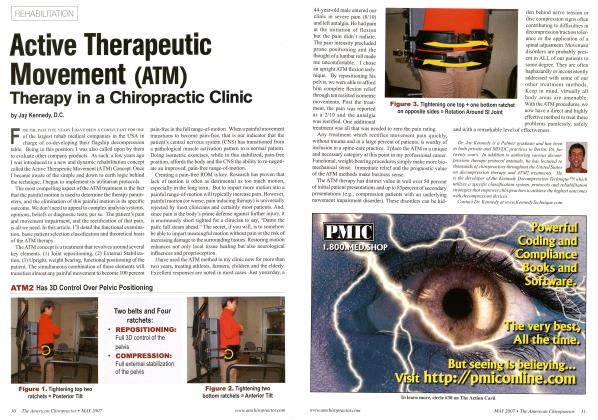

With our decompression technique, we regularly utilize the McKenzie directional-preference assessment and centralization phenomena to determine the table position and to what extent that extension may be beneficial. Since many tests and procedures have failed to measure up under scrutiny, it’s important to use those that tend toward being evidenced-based.7 If extension posture (simply lying prone or propped up on the elbows) gives modest or dramatic relief to leg or back pain, it becomes determinative to the ideal decompression posture, i.e. prone or prone with torso inclination. In this regard, it’s important to note a table designed to bend at the waist—not mid-sternum—is the most practical and biomechanically feasible. It’s important to mimic the actual relieving position when on the table, not just to lie face down. Having an electric-table system is a necessity in finding this “sweet spot” easily and nontraumatically (for both doctor and patient), and being able to alter it as needed during treatment. Sometimes the ideal position is just a few inches one way or another, and such positions are difficult to safely reach if you are using manual, mechanical-lock table sections.

From these motion tests, the assessment that prone-position decompression is likely the most rational treatment choice becomes evidence-based and prepares the spine for the proper force distribution. Regrettably, it is nearly impossible to rectify supine-only decompression systems with the published and empirical research available. It seems as though there is an abrogation of science behind

building in this limitation. Supine positioning certainly has its place, but it is never exclusive. We disagree as well with the contention that circumduction and lateral bending are necessary features. This is due to their negative effects on the neural tissues and nucleus (creating adverse annular compression), as well as the fact they are promoted for acute-pain positioning (a point in the injury cycle when axial-traction should be avoided).

Patient classification-to-positioning has been and continues to be a most important aspect of evidence-based care. A 2018 study published in the American Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation titled “Mechanical Traction for Radicular Symptoms: Supine or Prone? A Randomized Controlled Trial” supports the use of the prone position as more efficacious than supine.8 Their conclusion states that “the addition of traction in the prone position along with other modalities resulted in larger and immediate improvements in terms of pain and disability.” The 2007 study by Fritz et al. in the Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy also chose the prone position with a bias toward caudal flexion to accommodate nerve-tension signs. The study’s authors chose the prone position based on “expert opinion consensus.”

So there are several important considerations for prone versus supine posture. Obviously, the tolerance of lying

"When extensive disc desiccation has occurred and the operative deformability of the disc is gone, then position ceases to be as anatomically vital."

prone is certainly one of them. However, many patients are tolerant of either posture, so there must be more to it and, therefore, further assessment of prone lying, prone prop-up, and/or prone press-up becomes instrumental. We have concluded after nearly 30 years of our clinical traction research that disc hydration, and thus, disc “mobility” (maintenance of its isotropic properties—its deformability), is the internal decider as to extension being of distinct benefit. If the disc has turgor, and when subjected to dynamic changes in compression and tension can and will deform, then table position matters a lot. When

extensive disc desiccation has occurred and the operative deformability of the disc is gone, then position ceases to be as anatomically vital. When nerve tension or foraminal occlusion is apparent, flexion must be utilized, at least initially, because the patient may simply be unable to remain on the table. This prone-flexion moment is an attribute of the table, i.e., the caudal section can be declined up to 40 degrees. The age and degenerative status (and nerve signs) give important input. Younger patients (under 55) demonstrating extension preference will be treated with prone-to-flexion relief, while older or nonreducible derangements are positioned supine.

Table-design attributes, viable, evidenced-based testing, and noninjurious treatment protocols assure the best outcomes and the least dissatisfaction. We all know we can’t fix everybody, but it’s vital that everyone we treat with the best positioning option, treatment protocol, and pre/post treatment modalities available.

References:

1. Evidence for use ofan extension-mobilization category in acute low back syndrome: a prescription validation pilot study. Delitto A et al. Phys Ther Apr; 73(4) 1993.

2. Treat your own back. Robin McKenzie. Spinal publications New Zealand limited. 1979.

3. The McKenzie methodfor low back pain: a systematic review. Machado L et al. Spine Apr 20; 2006.

4. Mechanical lumbar traction: what is its place in clinical practice? JOSPT 46(3) 2016.

5. A comparison ofPT, chiropractic manipulation and educational booklet for treatment ofpatients with low back pain. Cherkin D et al. NEngl JMed Oct (8) 1998.

6. Tow back disorder 3rd edition. Human Kinetics. Stuart McGill PhD. 2006

7. A review of the evidence for the effectiveness, safety and cost of acupuncture, massage and manipulation for back pain. Cherkin D et al. Comp and Alt med. 2003.

8. Mechanical traction for lumbar radicular pain: supine or prone? A RCT. Bilgilsoy Flitz M et al. Am Jphys med rehbil Jan(5) 2018.

9. The effectiveness of the McKenzie method in addition to fir st-line care for acute low back pain: a RCT. Machado L et al. BMC Med Jan 26(8) 2010.

Jay Kennedy, DC, is a 1987 graduate of Palmer Chiropractic College and maintains afull time practice in western Pennsylvania. He is the principal developer of the Kennedy Decompression Technique. Dr. Kennedy teaches his non-machine specific technique to practitioners who want to learn clinical expertise required to apply this increasingly mainstream therapy. Kennedy Decompression Technique Seminars are approved for CE through various Chiropractic Colleges. The author can be contacted @ decompression, (afiennedytechnique, com.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue