Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms (AAA) are potentially life-threatening conditions with the mortality rate approaching 90 percent following rupture. The incidence of AAA is higher in individuals with hypertension, advanced age, and a history of smoking, and the rate of rupture is directly related to aneurysmal size and rate of enlargement. Screening of patients with risk factors of AAA and appropriately scheduled follow-up imaging of patients with a known history of abdominal aortic aneurysm is essential.

Discussion

An aneurysm is generally defined as a localized permanent dilatation of a vessel measuring at least 1.5 times its normal diameter. Most aneurysms occur in the aorta or other arteries, although some occur in locations such as the venous system and the heart. Certain aneurysms such as Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms (AAA) are more prominent in males, being up to 6 times more common in men than in women 1,2. Other aneurysm types such as splenic or cerebral artery aneurysms are equally prevalent in both men and women3. Most aneurysms cause no symptoms and do no harm4. It is not clearly understood what causes their development, however, hypertension, atherosclerotic disease, and cigarette smoking are among the commonest factors increasing their risk of development5. Genetic influences and congenital disorders may also play a role in their formation 6,7. Regardless of location or etiology, histologic samples of aneurysmal tissue typically demonstrate a decrease in collagen content that could be related to a weakness of the wall underlying the disorder8.

Aortic Aneurysms

The aorta is the most common location of an aneurysm. Aneurysms within the thoracic cavity are termed thoracic aortic aneurysms, while aneurysms found within the abdominal cavity are termed abdominal aortic aneurysms. In addition to the general definition of an aneurysm being a permanent dilatation of 1.5 times the normal vessel diameter, aortic aneurysms can also be defined as the infrarenal aortic diameter of > 3cm. A less commonly used measurement describes the aorta with an infrarenal-to-suprarenal diameter ratio of > 1.2 cm as an aortic aneurysm 9. Approximately 80% of aortic aneurysms occur between the renal arteries and the aortic bifurcation10.

Causes of Aortic Aneurysms

Aortic aneurysms develop secondary to a variety of factors. While there is strong evidence linking certain factors to their development, other causes are often not as clear. Forsdahl, et al demonstrated strong associations between the risk of incidence of abdominal aortic aneurysm and traditional atherosclerosis risk factors such as cigarette smoking (>20 cigarettes/day), hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia11. Blanchard et. al, however, found no association between cholesterol and AAA12.

Degenerative dilation of the aortic wall is among the commonest causes of aortic aneurysm development. This is a result of a decrease in the elasticity of the aortic tissue causing weakening of the region and leading to aneurysmal development. Atherosclerotic plaque is a major contributor, leading to damage of the arterial media and subsequent vessel dilation 13.

Genetic diseases such as Marfan’s Syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, Loeys-Dietz, and Turner Syndrome correlate with a higher risk for the development of an aneurysm due to their collagen abnormalities and subsequent potential weakening of the aortic wall7.

Severe chest or abdominal trauma may cause damage to the wall of the aorta leading to late aneurysmal formation. There is also increasing evidence that inflammation may play a role in the development of aneurysmal growth and rupture14,15. Bicuspid aortic valves can produce chronic dilatation of the ascending aorta which can lead to the development of an aneurysm16.

Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms

Abdominal aortic aneurysms are present in approximately 1% of men aged 55 to 64 years, and the prevalence increases by 2% to 4% per decade thereafter. Abdominal aortic aneurysms are four to six times more common in men than in women, and men tend to develop these approximately 10 years earlier than women10. There is an estimated 15-25% prevalence of AAA in persons who have immediate family members with an abdominal aortic aneurysm 17.

Most AAAs are asymptomatic, and many are detected as incidental findings on a physical exam or on imaging studies obtained for other reasons. Diagnostic imaging is a highly sensitive tool for aortic aneurysm detection and monitoring.

Diagnostic Imaging

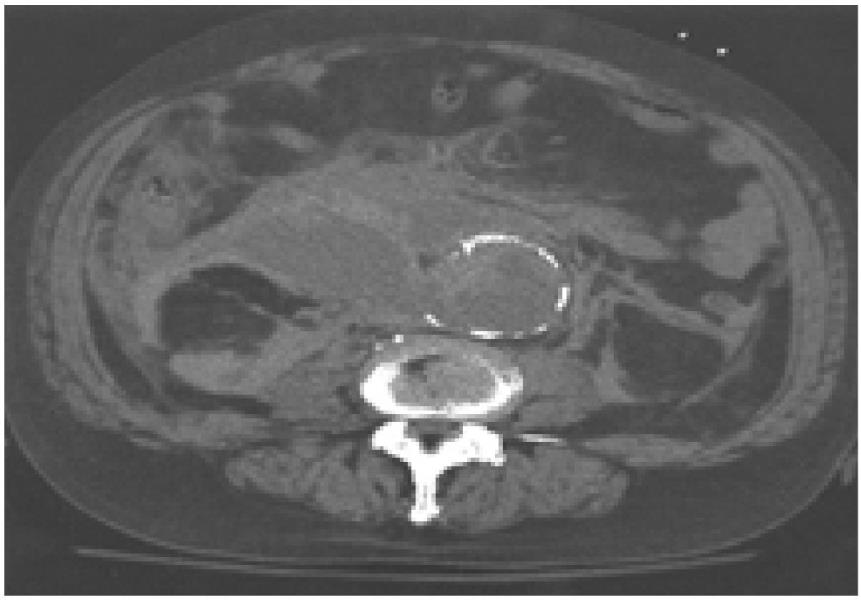

CT demonstrating ruptured AAA

CT demonstrating ruptured AAA

Ultrasonography is the standard method for screening and follow-up of aortic aneurysms (Figure 1) (Figure 2). It has a number of advantages over other imaging modalities, including the ability to be performed in-office or bedside, and using sound waves rather than ionizing radiation. Ultrasonography has a specificity and sensitivity approaching 96 and 100 percent respectively for the detection of infrarenal aortic aneurysms18. Ultrasonography, however, does have limitations. It is less accurate for smaller aneurysms and consistently gives a smaller reading of aortic diameter when compared with CT measurement19. Sonography is not indicated if there is suspicion of a leak or aneurysmal rupture. It is also limited in obese patients or those with abundant overlying bowel gas. In addition, the renal arteries are rarely visualized directly, and suprarenal extension can frequently only be inferred by the relationship of the aneurysm to the superior mesenteric artery20.

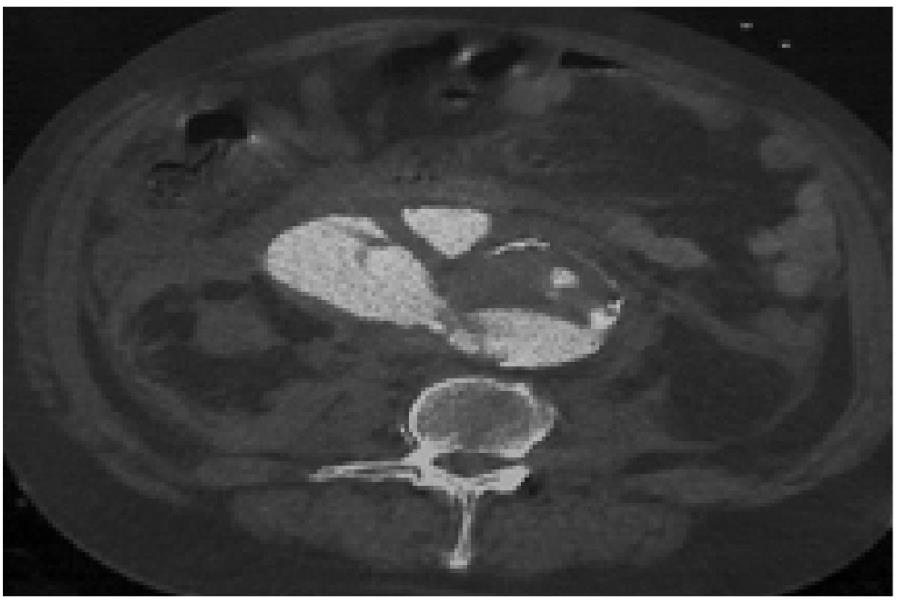

Computed tomography (CT) offers certain advantages over ultrasonography in providing a more accurate measurement of aortic size and a better rostral-caudal evaluation19. It is also useful for aortic dissection, demonstrating a sensitivity of 87-94% and a specificity of 92-100%21. CT may be performed with or without contrast, with contrast being necessary to demonstrate dissection or a mural thrombus and to better demonstrate extravasation of blood from a ruptured aneurysm (Figure 3) (Figure 4). Contrast-enhanced CT is contraindicated in patients with allergies to contrast, renal disease, and elevated creatinine levels. Magnetic resonance imaging permits imaging of the aorta comparable to that obtained with CT without subjecting the patient to ionizing radiation17. Disadvantages include increased cost, patient claustrophobia, and potential motion artifact, and MRI may not be as readily available in an acute setting22. Aortic anomalies may cause confusion in interpretation, and misinterpretations of false-positive aortic dissection are occasionally seen in gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance angiography (MRA)21.

CT with contrast demonstrating ruptured AAA

CT with contrast demonstrating ruptured AAA

Plain film radiographs are not optimal for detection or follow-up. While an aneurysm may be visible on x-ray as dilated or curvilinear aortic calcifications, only approximately 55-85% contain enough calcium to be detected on plain films. Once an aneurysm is suspected from plain films, advanced imaging is required for a more thorough evaluation20.

Clinically significant AAAs, those larger than 4 cm in diameter, are often palpable on routine physical examination, although a large body habitus may interfere with its detection. The presence of a pulsatile abdominal mass is virtually diagnostic but is found in only about one-third of all cases10. Cabellon et al, demonstrated that in patients with known peripheral atherosclerotic vascular disease, physical exam demonstrated a 2.6 percent incidence of AAA whereas ultrasonography established the incidence at 9.6 percent23.

Abdominal aortic aneurysms are generally asymptomatic until they expand or rupture. An expanding AAA may cause sudden, severe, and constant low back, flank, abdominal, or groin pain. However, occasionally syncope may be the chief symptom. Aneurysms that produce symptoms such as pain and tenderness on palpation are at increased risk for rupture. Patients with a ruptured AAA classically present with hypotension along with shooting abdominal or back pain and a pulsatile abdominal mass10.

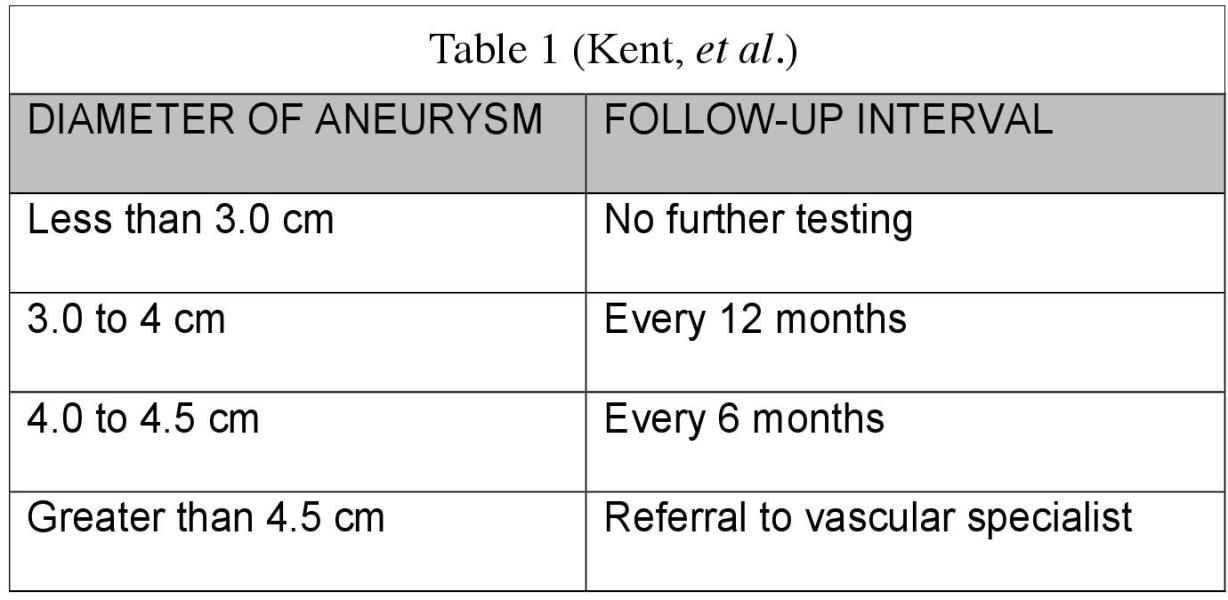

The mortality rate of AAA rupture approaches 90 percent. Of these ruptures, 65 to 75 percent of patients die of sudden cardiovascular collapse before they arrive at the hospital, and up to 90 percent die before they reach the operating room.24,25,26 Patients with a known history of AAA should be monitored for changes in the size of the aneurysm. Kent et al, provided guidelines for ultrasound follow-up of known AAA based upon the aneurysmal diameter (18) (Table 1). They demonstrated that no follow-up is necessary for aneurysms of less than 3.0cm. However, for aneurysms from 3.0 to 4.0cm follow-up ultrasound of the aneurysm, every 12 months should be performed. They further recommend that for aneurysms ranging from 4.0 to 4.5 centimeters follow-up ultrasound be performed every six months. Abdominal aortic aneurysms measuring greater than 4.5 cm should be referred to a vascular specialist for evaluation.

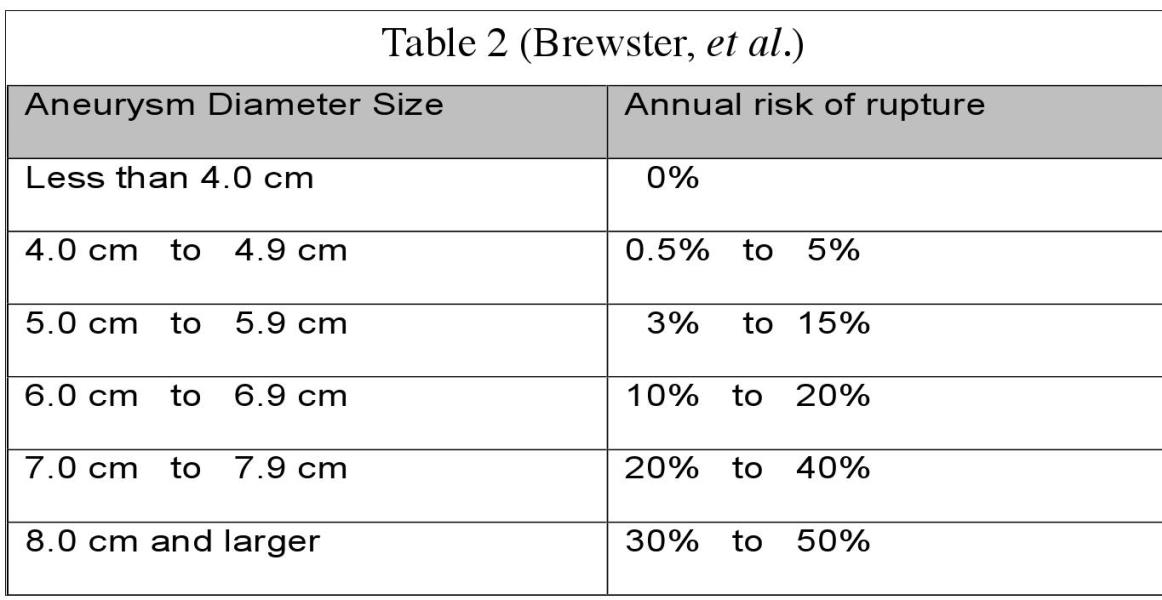

The risk of rupture is directly related to both size and rate of expansion27 (Table 2) and repair is indicated for AAAs greater than 5.5 cm in diameter or those which enlarge more than 0.6 to 0.8 cm per year28. Brewster et al describe an annual aneurysmal rupture risk based upon the size of the aneurysm. It is well understood, however, that abdominal aortic aneurysms do not rupture solely based upon their size. While size and rate of expansion are primary concerns, other factors may also play a predictive role in rupture. Cronenwett, et al observed that increased initial diameter, hypertension, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) were independently predictive of rupture in patients with small AAAs29. Sterpetti, et al concluded that larger initial AAA size, hypertension, and bronchiectasis were independently associated with AAA rupture30.

Conclusion

Abdominal aortic aneurysms are typically asymptomatic and often found incidentally. The incidence of AAA is higher in men, individuals over 60 years old, and smokers, and factors such as hypertension, genetic causes, and congenital changes also increase the incidence of developing an AAA. There is a mortality rate approaching 90 percent with aortic aneurysm rupture. A direct relationship exists between aneurysmal size and rate of rupture, however other factors such as rate of aneurysmal enlargement, hypertension, and pulmonary issues are also implicated. It is essential that appropriate evaluation be conducted on high-risk individuals, and scheduled monitoring be performed for those with a known history of an aneurysm.

Gregory Katsaros, DC, DAAPM is the owner of Integrative Pain Management in Tempe, Arizona. He is a member of the American College of Nuclear Medicine and the International Headache Society. His practice focuses on headaches and nonsurgical musculoskeletal pain. His website is www.azheadaches.com. He can be reached at [email protected]

References

1. Pleumeekers HJCM, Hoes AW, van der Does E, van Urk H, Hofman A, de Jong PTVM, Grobbee DE. Aneurysms of the abdominal aorta in older adults. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;142:1291-1299.

2. Scott RAP, Bridgewater S, Ashton HA. Randomised clinical trial of screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm in women. Br J Surg. 2002;89:283-285

3. Norman PE, Powell JT. Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm-The Prognosis in Women Is Worse Than in Men. Circulation; June 7, 2007; http://dx.doi. org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA .106.671859

4. Aneurysm. In: Ritchie AC, editor. Boyd's Textbook of Pathology. 9th edition. Philadelphia!London:1990; p. 645-652.

5. Fleming C, Whitlock EP, Bell TL, Lederle FA. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm: a best-evidence systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Sendees Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:203-11.

6. Baird PA, Sadovnick AD, Yee IM, Cole CW, Cole L. Sibling risks of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Lancet Sept, 1995: 346 (8975): 601

7. Cury M, Zeidan F, A. Aortic Disease in the Young: Genetic Aneurysm Syndromes, Connective Tissue Disorders, and Familial Aortic Aneurysms and Dissections. Int J Vase Med. 2013; 2013: 267215. http://dx .doi:10.1155/2013/267215

8. de Figueiredo BE, Jaldin RG, Dias RR, Stolf NA, Michel JB, Gutierrez PS. Collagen is reduced and disrupted in human aneurysms and dissections of ascending aorta. Hum Pathol. 2008 Mar;39(3):437-43. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath .2007.08.003.

9. Naydeck B, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Schiller, K, Newman A, Fuller L. Prevalence And Risk Factors of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm In Older Adults With and Without Isolated Systolic Hypertension. Am J Cardiol 1999: 83:759-764

10. Aggarwal S, Qamar A, Sharma V, Sharma A. Abdominal aortic aneurysm: A comprehensive review. Exp Clin Cardiol. 2011 Spring; 16(1 ): 11-15.

11. Forsdahl SH, Singh K, Solberg S, Jacobsen BK. Risk Factors for Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms A 7-Year Prospective Study: The Tromsp Study. 1994-2001; Circulation; April 28, 2009. http://dx.doi. org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA .108.817619

12. Blanchard JF, Armenian HK, Friesen PP. Risk factors for abdominal aortic aneurysm: results of a case-control study. Am J Epidemiol. 2000 Mar 15.151(6):575-83. [Medline].

13. Golledge J, Norman PE. Atherosclerosis and Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Cause, Response, or Common Risk Factors. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2010; 30:1075-1077 doi:10.1161/ ATVBAHA.110.206573

14. Bacharach JM, Garratt KN, Rooke TW. Chronic traumatic thoracic aneurysm: Report of two cases with the question of timing for surgical intervention. Journal of Vascular Surgery; April 1993 Volume 17(4): 780-783.

15. Fattori R, Russo V. Degenerative aneurysm of the descending aorta. Endovascular treatment. Multi-Media Manual of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery; mmets .2007.002824 January 1, 2007

16. Tadros TM, Klein MD, Shapira OM. Ascending Aortic Dilatation Associated With Bicuspid Aortic Valve - Pathophysiology, Molecular Biology, and Clinical Implications. Circulation. February 17, 2009

17. Rahirni SA, Rowe VL. Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm: Medscape: emedicine .medscape .com/article/1979501 -overview#a6

18. Kent KC, Zwolak RM, JaffMR, Hollenbeck ST, Thompson RW, Schermerhorn ML, et al. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Vase Surg. 2004;39:267-9.

19. Thomas PRS, Shaw JC, Ashton HA, Kay DN, Scott RAP. Accuracy of ultrasound in a screening programme for abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Med Screening 1994;1:3-6.

20. LaRoy LL, Cormier PJ, Matalon TAS, Patel SK, Turner DA, Silver B. Imaging of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms. AJR April 1989, 152:785792. doilpdfll0.2214lair.152.4.785

21. Khan AN, Macdonald S. Aortic Dissection Imaging.emedicine.medscape .com/article/416776-overview#a4

22. Sparks AR, Johnson PL, Meyer MC. Imaging of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms. Am Fam Physician. 2002 Apr 15;65(8):1565-1570.

23. Cabellon Jr S, Moncrief CL; Pierre DR, Cavanaugh DG. Incidence of abdominal aortic aneurysms in patients with atheromatous arterial disease: American Journal of Surgery: November 1983 Vol 146(5): 575-576

24. Rahirni SA, Rowe VL, Annambhotla S, et al; Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm. Medscape; Nov 19, 2014

25. Kent KC (27 November 2014). “Clinical practice. Abdominal aortic aneurysms.”. The New England Journal of Medicine 371 (22): 2101-8. doi:10.1056/NEJMcpl401430

26. Brown LC, Powell JT (September 1999). “Risk Factors for Aneurysm Rupture in Patients Kept Under Ultrasound Surveillance”. Annals of Surgery 230 (3): 289-96; discussion 296-7.

27. Brewster DC, Cronenwett JL, Hallett JW, Jr, et al. Guidelines for the treatment of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Report of a subcommittee of the Joint Council of the American Association for Vascular Surgery and Society for Vascular Surgery. J Vase Surg. 2003;37:1106-17.

28. Upchurch GR, Schaub TA. University of Michigan Health System, Ann Arbor, Michigan; Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm; Am Fam Physician. 2006 Apr 1;73(7) :1198-1204.

29. Cronenwett, JL, Sargent, SK, Wall, MH, Hawkes, ML, Freeman, DH, Dain, BJ et al. Variables that affect the expansion rate and outcome of small abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Vase Surg. 1990; 11: 260-269.

30. Sterpetti, AV, Cavallaro, A, Cavallari, N, Allegrucci, P, Tamburelli, A, Agosta, A et al. Factors influencing the rupture of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1991; 173:175-178

View Full Issue

View Full Issue