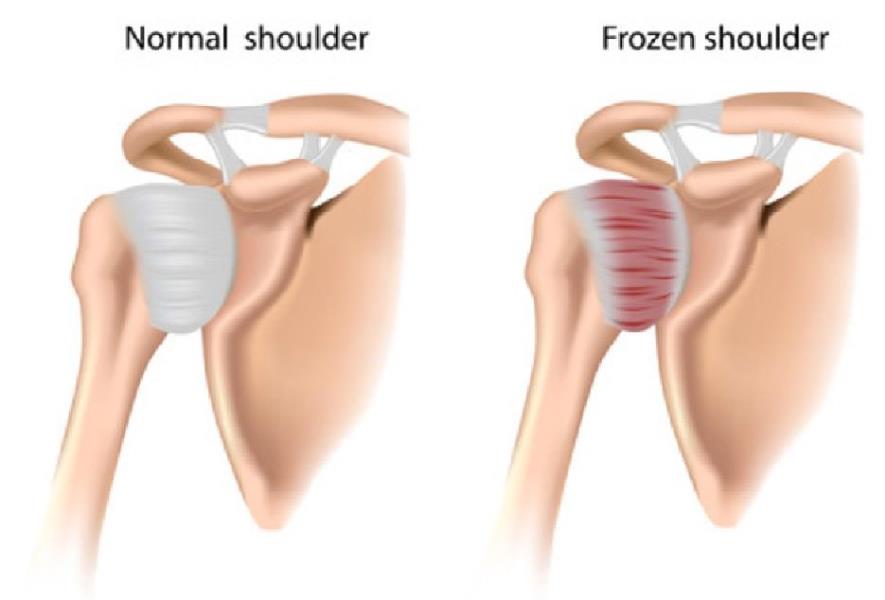

Frozen shoulder (FS) is a common disorder characterized by a gradual increase of pain and limitation in range of motion of the glenohumeral joint. The pathophysiology of FS is relatively well understood as a pathological process of synovial inflammation followed by capsular fibrosis. However, the cause of FS is still unknown because the patient cannot elevate the shoulder, and the clinician cannot elevate it either. Treatment modalities for FS include medication, local steroid injection, physiotherapy, and manipulation under anesthesia, even though FS has been regarded traditionally as a self-limiting and benign disease with complete recovery of pain and ROM in nine months to one year.

However, this condition can sometimes last for years. In one study, 50% of patients were still experiencing pain or stiffness of the shoulder at a mean of seven years from the onset of the condition, although only 11% reported functional limitation. In a prospective study of 41 patients with 5 to 10 years1 of follow-up, Reeves found that only 39% of patients had a full recovery. This long period of pain and disability deprives patients of their routine life and occupational and recreational activities. Appropriate treatment is needed for a rapid return to their own life.

FS can be divided into three phases—freezing (insidious onset of shoulder pain with progressive loss of motion), frozen (gradual subsidence of pain, plateauing of stiffness with equal active and passive ROM), and thawing (gradual improvement of motion and resolution of symptoms).2 Macroscopic findings include thickening and congestion of the capsule with an inflamed appearance, particularly around the rotator interval of the coracohumeral ligament and middle glenohumeral ligaments (Fig. 1).3 Microscopically, the affected capsule has a higher number of fibroblasts, mast cells, macrophages, and T cells. This synovitis is associated with increased fibrotic growth factors, inflammatory cytokines, and interleukins.4

50% of patients were still experiencing pain or stiffness of the shoulder at a mean of seven years from the onset of the condition

Radiographic Findings

Evaluation and clinical presentation of patients presenting with adhesive capsulitis will often report an insidious onset with a progressive increase in pain and a gradual decrease in active and passive range of motion.4

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

One of the main presenting factors is loss of external rotation (ER) with a coupled loss of abduction (Abd)

Patients frequently have difficulty with grooming, performing overhead activities, dressing (particularly fastening items behind the back), and general activities of daily living.

Effects of Radial Pulse Therapy

• Vasodilates avascular structures and brings new blood into existing vascular structures.

• Initiates a destructuring and restructuring of the intratendinous formations.

• Stimulates tenocytes, fibroblastic activity, and reorganizes collagen III-I.

• Modulates any thickening (proinflammatory) secondary to reaction.5

Methodology Utilizing Radial Pulse Therapy

Each treatment was divided into three regions, but with FS, I added one additional region (axilla, internal capsule). The following was my approach to treatment:

Patient Population

The cross-section representing this study was limited to four patients in good health—three males and one female, ages 52 to 64. All shared a history of manual labor throughout their lives.

They came from India, U.K., Australia, and the U.S. Since these cases, I have treated 12 other patients utilizing the same protocol and have achieved very favorable, successful outcomes.

Treatment durations

4,000 to 6,000 pulses per week (utilized by clinicians globally for optimum outcomes)

Administering Pulses

(Note: pain threshold must be 7/10 on VAS scale for the first 2,000 pulses)

Patient position: Supine on treatment with the ability to be in prone and side postures.

Conclusion

For the several patients I have treated using this technique, the average number of treatments was four to six with complete resolution. However, performing radial pulse therapy alone without loading exercises produced only a 60-70% success rate. Loading exercises in conjunction with the shockwave was the key step in the treatment process for 100% resolution.

Dr. Farley Brown earned his doctorate in Chiropractic Medicine with an emphasis in Clinical Orthopedics, Therapeutic Exercise, and Pain Management from the Southern California University of Health Sciences in Los Angeles (formerly known as LA College of Chiropractic). After practicing Chiropractic and Physical Therapy for more than two decades, Dr. Brown became a clinical education manager and product development consultant for several corporations, most notably a 10-year stint with DJO Global in Vista, California.

References:

1. Orthopedics Jama Network December 16, 2020. Comparison of Treatments for Frozen Shoulder A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Dimitris Challoumas, MD1; Mairiosa Biddle, MD1; Michael McLean, MD1; et al

1. World Journal Orthopedics 2015 Mar 18; 6(2):263-268. Published online 2015 Mar 18. doi:10.5312/wjo.v6.i2.263. PMCID: PMC-1363808. PMID: 25793166. Frozen shoulder: A systematic review of therapeutic options. Harpal Singh Uppal, Jonathan Peter Evans, and Christopher Smith.

2,3. Clinical Guidelines in the Management of Frozen Shoulder: An Update!. Vivek Pandey & Sandesh Madi. Indian Journal of Orthopaedics (2021) Cite this article.

4. The pathophysiology associated with primary (idiopathic) frozen shoulder: A systematic review. Victoria Ryan, Hazel Brown, Catherine J. Minns Lowe & Jeremy S. Lewis. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders volume 17, Article number: 340 (2016).

5. The biological effects of extracorporeal shock wave therapy (eswt) on tendon tissue. Angela Notarnicola and Biagio Moretti. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2012 Jan-Mar; 2(1): 33-37.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue