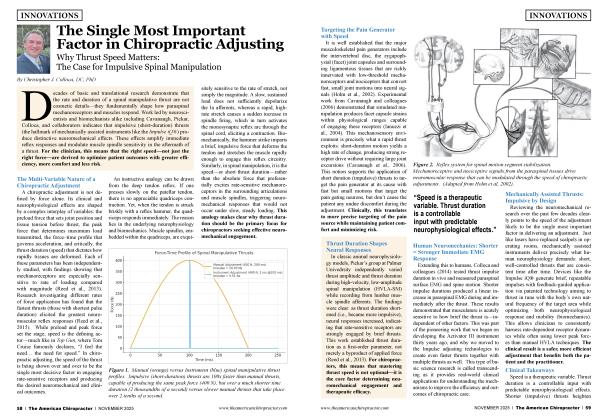

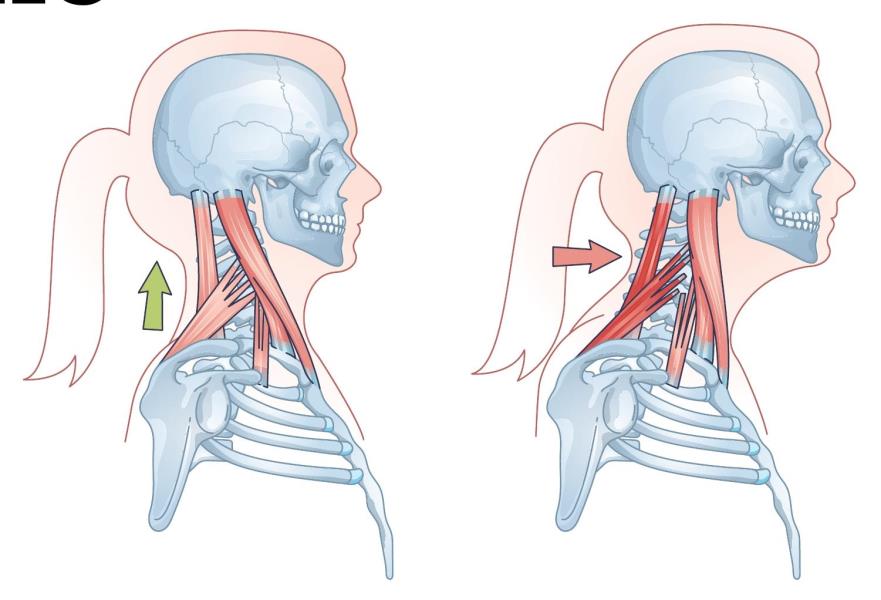

FORWARD HEAD POSTURE (FHP), or anterior head carriage, is one of the most common structural patterns chiropractors encounter and one of the simplest to demonstrate. A side-view image showing the ears positioned forward of the shoulders tells the story in seconds.

From there, we can begin to educate patients on the degree of displacement and the cumulative impact on biomechanics and function. The opportunity lies in turning this visible misalignment into a gateway for whole-body correction.

On lateral cervical X-rays, anterior head carriage is among the most frequent findings, even in asymptomatic cases. It often accompanies a hypolordotic or straightened cervical curve, and it’s not exclusive to patients with neck complaints. We see it across the board in cases of low back pain, midback tightness, and hip dysfunction, regardless of where the patient’s symptoms present.

The danger of overlooking FHP is that it may not hurt until it does. Chiropractors must remain vigilant not to tie their attention solely to pain, especially when posture patterns like this one can persist for years and drive deeper dysfunction.

What may begin as a singular misalignment can turn regional before becoming a broader postural distortion. Cervical and upper thoracic vertebrae may all contribute to subluxation on the examination.

The pattern doesn’t stop at bone position, though. Chronic forward head posture leads to muscle imbalance. Flexor groups dominate; extensors weaken. A neuromuscular tug-of-war develops, making true correction more complex than a single adjustment.

This is when the chiropractic approach can shine. When we address subluxation and facilitate better proprioception, we begin to unwind a pattern that affects the entire kinetic chain.

FHP can be the primary problem, but it’s often compensation. In a whole-body assessment, three findings consistently stand out: anterior head carriage, pelvic tilt, and asymmetrical foot pronation.

These may coexist or cascade from one another, but their relationship is essential. In these cases, foot dysfunction, particularly the collapse of one or more arches, is often the root issue. Without evaluating the foundation, cervical corrections may become temporary relief rather than lasting change.

We perform digital foot scans on every new patient, not as a secondary screen but as a required component of our wholebody posture analysis. The data provides objective insight into how a person stands, moves, and compensates, and more importantly, what support they may need to maintain spinal correction.

From a functional standpoint, the consequences of FHP extend well beyond the neck. Breathing becomes strained. Ask anyone to push their head forward and take a deep breath, and they’ll feel the restriction instantly.

The diaphragm can’t engage properly, and accessory muscles dominate the effort. Over time, shallow breathing becomes the norm.

This reinforces a stress signal to the nervous system. Subconsciously, the body interprets this restricted, neck-dominant pattern as a state of chronic threat.

Add the role of proprioception joint feedback relayed constantly to the brain, and it’s clear that FHP introduces neurological confusion at a fundamental level. Poor breathing, poor balance, and poor feedback are a dangerous combination for any system under load.

We rely heavily on digital photography as part of our initial and ongoing assessments. Patients must see it to believe it, and when posture data is visually reinforced, engagement improves. Weight-bearing X-rays and foot scans, along with examination, complete the triad of functional diagnostics, giving us multiple perspectives on how FHP fits into the broader aligmnent picture.

These tools also help guide the timeline of care. By the second visit, we often begin extremity adjustments. By the third visit, custom functional orthotics are introduced. From that point forward, home care begins with breath control exercises and movement retraining, specifically while wearing orthotics to establish a new baseline.

We teach posture as a primary health strategy, not just an add-on. Every patient receives guidance on breath control and balance training as foundational practices. Whether they’re walking, climbing stairs, or rowing, the mechanics of breath and balance should align with spinal integrity.

We bring the focus back to functions that follow them through every activity. When you teach people how to walk and breathe in ways that support spinal health, you create a platform for everything else — better exercise, better recovery, better stress resilience.

From a preventive standpoint, we see FHP as a contributor to chronic stress and, therefore, chronic disease. Whether stress is chemical, emotional, or physical, posture is a common denominator.

When left uncorrected, forward head posture becomes an amplifier of physical tension, emotional fatigue, and neurological overload. Inversely, correcting it becomes a means of interrupting that cycle and restoring adaptive potential.

When the public talks about health indicators, they think of labs, vitals, and risk factors. We believe anterior head carriage belongs on that list.

It is visible, measurable, and correctable — often before symptoms begin. It should be screened routinely and explained clearly. Forward head posture isn’t just about discomfort; it’s a signpost of imbalance.

If a colleague asks me what I think about FHP, I’ll tell them it’s one of the clearest postural indicators of nervous system stress and one of the most easily missed. It deserves our clinical attention because of where the head sits and everything it tells us about the rest of the body. The neck doesn’t float in space; it balances on a chain of structures that often begin failing at the feet.

FHP should be as commonly addressed as any spinal subluxation, and just as thoroughly explained. In a world where patients are exposed to more stress, more devices, and more sedentary hours, we must lead the effort to recognize postural dysfunction early and empower people to correct it before it becomes a chronic disease.

Anish Bajaj, DC, is a 2000 graduate of Life University in Atlanta, Georgia. He is the owner of Well Rooted Health & Chiropractic in New York City and Westfield, New Jersey. He serves on the executive board of the New York Chiropractic Council as chair of the Neuroscience and Research Committee. As a member of the Foot Levelers Speaker’s Bureau, he travels extensively, sharing chiropractic knowledge and expertise with audiences across the country. To learn more, visit FootLevelers.com/more.

References

1. American Posture Institute. Posture and breathing: The hidden connection. 2017. Available at: https://www.americanpostureins... posture-breathing/

2. Dahlqvist J, Hansson EE. Forward head posture and its implications for health and function. Journal of Bodwork and Movement Therapies. 2020;24(3):232-238. https://doi.org/10.1016/jjbmt....

3. Harrison DE, Harrison DD, Janik TJ, Cailliet R, Holland B. Reliability of the posterior tangent method for sagittal cervical spine alignment analysis. Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics. 1999;22(5):309-314. https://doi.org/10.1016/80161-...

4. Kang JH, Park RY, Lee SJ, Kim JY, Yoon SR, Jung KI. The effect of the forward head posture on postural balance in long time computer based worker. Ann Rehabil Med. 2012 Feb;36(l):98-104. doi: 10.5535/ arm.2012.36.1.98. Epub 2012 Feb 29. PMID: 22506241; PMCID: PMC3309315.

5. Raine S, Twomey LT. Head and shoulder posture variations in 160 asymptomatic women and men. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1997 Nov;78(ll):1215-23. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(97)90335-x. PMID: 9365352.

6. Subtelny JD. The significance of head posture in orthodontics. The Angle Orthodontist. 1959;29(3): 179-186. https://doi. org/10.1043/0003-3219(1959)029<0179:TSOHPI>2.0.CO;2

7. Yip CH, Chiu TT, Poon AT. The relationship between head posture and severity and disability of patients with neck pain. Man Ther. 2008 May; 13(2): 148-54. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2006.11.002. Epub 2007 Mar 23. PMID: 17368075.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue