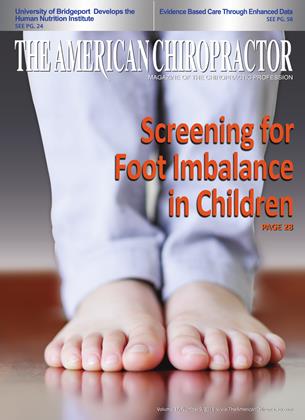

Screening for Pedal Imbalance in Kids

TECHNIQUE

John K. Hyland

Foot problems that develop in childhood can have both immediate and long-term effects. During growth, the normal development of the pelvis and the spine will suffer if there is a foot imbalance. The sports performance of youngsters—and even running at recess—can be affected significantly. Later in life, foot problems from childhood can interfere with spinal function, which can result in poor biomechanics and accelerated degenerative changes in the knees, hips, and spine. With a relatively quick screening of their young patients, doctors of chiropractic can identify those who need intervention, and then provide proper orthotic support.

Normal Development of the Foot

During early development, and especially as we begin to walk, the lower extremity changes significantly. The legs undergo rotation in order to allow the feet to align with the knees and hips for a smooth gait. The arches slowly become more obvious and increase in height as our gait improves. The foot grows faster than the rest of the body; it achieves three-quarters of its mature length by the time the child is seven years old.(1) Most problems arise when the feet and legs do not align properly (intoeing or out-toeing), or when the main longitudinal arch does not develop fully.

Intoeing/out-toeing. Studies over the past couple of decades have shown that shoe modifications, such as wedges, special lasts, and corrective orthotics, have no significant predictable effect on children with intoeing or out-toeing. 23 Exercising the involved external (or internal) rotation muscles (to accelerate or stabilize the normal developmental rotation of the leg) may be useful, but has not been tested reliably. At this point, the best recommendation for most kids is to wear good shoes and to focus on sports and activities that develop balanced leg muscles. When there is a family history of poor foot/leg alignment, custom-fitted orthotics may be of some benefit, primarily in improving biomechanical function and coordination during sports performance.

Flatfoot. The longitudinal arch normally develops during the first six to 10 years of growth. The reduced incidence of flatfoot

■ "Parents should be encouraged to let children go barefoot whenever it is safe and to select shoes based on function, not just on style or cost. 5 5

seen in studies of barefoot populations (4'7) suggests that muscle strength and mobility are important factors in the normal development of the arches. This means that a child is more likely to develop a flexible yet strong arch when going barefoot. Wearing orthopedic shoes or arch inserts does not seem to influence the development of normal arches.(8) Parents should be encouraged to let children go barefoot whenever it is safe and to select shoes based on function, not just on style or cost.

Since the tendency for flatfoot is inherited, the source of many kids’ flatfeet can be traced to a paient or another relative. In these cases, it is especially important that the child spend a lot of time going barefoot. When this cannot be done safely or regularly, custom-fitted orthotics should be considered. Children who regularly engage in sports activities will benefit most.

Screening Exam for Kids

Watch the Child Walk

Look for foot flare (toe-out), toe-in, or other gait abnormality

Look at the Shoes

Check for excessive lateral heel wear or shoe breakdown

Check Knee-to-Foot Alignment

Medial facing (“squinting”) patellae or valgus knees

Look at the Achilles Tendons

Medial bowing is associated with an everted calcaneus

Palpate the Medial Arches

Check for lack of an arch and/or painful plantar fascia

Toe Raise Test for Flexibility

Rules out a rigid flat foot, as in tarsal coalition or equinus

Check for Subluxations

Adjust, then check for recurrence with walking

Screening Exam

Avery quick method for checking kids for the need for orthotics follows. While similar to the procedure I use for screening adults, some of the specifics differ. This lower extremity screening examination fits well into standard chiropractic examination procedures, and it can be performed easily on children down to ages five or six. When several red flags are present, I know

I will have to discuss the findings and the probable need for orthotics with the parents.

Watch the child walk. By observing a few normal, relaxed paces, several abnormal gait findings can be distinguished. With young patients, the most common fault is intoeing, followed closely by excessive toeing out (foot flare). This can be identified by looking at the alignment of the foot with the lower leg as your patient walks. An angle that is either less than 5 degrees or greater than 15 degrees is a red flag for excessive rotational torque stresses into the knees, sacroiliac joints, and spine.

Look at the shoes. Take a brief moment to inspect the wear pattern on the child’s shoes. Parents may need to be instructed to bring in a worn pair for better analysis. Look to see if there are any excessive or abnormal wear patterns present, either at the heels or in the upper, softer portions of the shoes. A red flag is any asymmetrical, excessive, or lateral wearing down of a heel, or a bulging or tearing of the shoe’s upper material.

Knee to foot alignment. Look at the lower legs of the child from the front. Mentally drop a straight line down from the midpoint of each kneecap to the foot. This imaginary plumb line should strike the foot over the first two metatarsals. If the knees point out or in when the feet are straight ahead, or if there is a valgus angulation (knock-knees), a red flag is raised.

Is the Achilles tendon straight? When you see a patient’s heel cord bowing inward (medially), you have a red flag that indicates probable instability of the calcaneus. When the heel does not align with the Achilles tendon, the child will develop into an overpronator, and this biomechanical fault will interfere with knee, hip, and spinal function over the decades.

Check the medial arches. If you cannot get your finger under the medial longitudinal arch, the child is not developing normal arches. While palpating the arch, take a moment to push upward into the plantar fascia. Even a brief palpati on will tell you if the connective tissue that supports the arch is intact or is under excessive strain. If this is painful to the child, it is possibly the sign of early plantar fasciitis, which is likely to still be at a stage where conservative biomechanical treatment will be rapidly helpful.

Perform a “toe raise.” If there is a lack of development of the medial arch, ask the child to do a toe raise. By standing up on the toes, the plantar fascia is put under tension, creating a temporary arch in patients with a flexible flat foot. If the foot remains flat (or becomes convex) in this position, it is likely that the child has a rigid flat foot. This is due to an anatomical fixation, such as a tarsal coalition or an equinus foot.

Check for recurring subluxations. Palpate and adjust any parts of the foot that aie not functioning normally. Ask the child to walk around the room a few times, and then check again. If the extremity subluxations that were just adjusted have returned, it demonstrates an underlying biomechanical problem that will need external support.

Orthotics for Kids

Children do not usually need custom orthotics until about the age of six. If at that point a child is still not developing a normal arch, or if intoeing persists, orthotics may be needed. This is particularly true when the child is involved in athletics and sports activities. In these cases, custom-fitted orthotic support for the arches can significantly improve gait and running performance. Otherwise, many children are well served by wealing sensible, flexible shoes.

When there is a family history of flatfeet or intoeing, I have found that a more aggressive use of orthotics is appropriate. Of course, the parents will need to be informed of the need to regularly refit the orthotics as the child’s foot grows.

Conclusion

With more research and experience, we know now that there are only a few rare cases of children who need special “orthopedic” or “corrective” shoes. Most kids will develop healthy leg, foot, and arch alignment as long as they are not forced into poorly fitted, inflexible shoes. We should encourage children to spend as much time as possible barefoot. The main concern when going without shoes is protection from cold, heat, and injury. Orthotics are very helpful for children who show evidence of persisting biomechanical problems

beyond the age of six. I use the screening examination described earlier to identify kids who need orthotic support. Those who are active in sports, or who demonstrate inefficient or awkward gait patterns, are especially good candidates for custom-fitted, corrective orthotics designed to support the developing arches of a child’s foot.

References

1. StaheliL. Corrective shoes for children: are they really necessary? J Pediatric Orthopaedics. 1997; 17:416.

2. Uden H. Kumar S. Non-surgical management of a pediatric “intoed” gait pattern—a systematic review of the current best evidence. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2012;5:27-35.

3. KnittleG, StaheliLT. The effectiveness of shoe modifications for intoeing. Orthop Clin North Am. 1976; 7:1019-1025.

4. ToengesF. Shoe therapy: past and present treatments. Clin Podiatr Med & Surg. 1997;14:209-214.

5. Hoffman P. Conclusions drawn from a comparative study of the feet of barefooted and shoe-wearing peoples. Am J Orthop Surg. 1905;3:105-136.

6. Engle ET, Morton DJ. Notes on foot disorders among natives of the Belgian Congo. J Bone Joint Surg. 1931;13:311318.

7. James CS. Footprints and feet of natives of the Solomon Islands. Lancet. 1939;2:1390-1393.

8. Sim-Fook L, Hodgson A. A comparison of foot forms among the non-shoe and shoe-wearing Chinese population. J Bone Joint Surg. 1958;40A: 1058-1062.

9. Wenger DR, et al. Corrective shoes and inserts as treatmentfor flexibleflatfoot in infants and children. J Bone Joint Surg. 1989;71-A:800-810.

A 1980 graduate of Logan College of Chiropractic, Dr. John Hyland practiced for more than 20 years in Colorado. In addition to his specialty board certifications in chiropractic orthopedics (DABCO) and radiology (DACBR), Dr. Hyland is nationally certified as a strength and conditioning specialist (CSCS) and a health education specialist (CHES). He has consulted chiropractors in the concepts and procedures of spinal rehabilitation and wellness exercise.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue