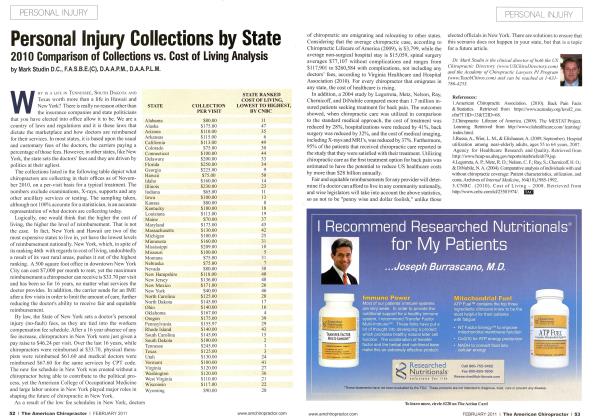

Being Guided by the Courts The courts in New York have some of the most difficult standards to determine if a patient has a serious injury. When determining if your patients have serious injuries, you should consider meeting the highest standard nationally when documenting their injuries, regardless of your state's requirements. This is not about being creative in documentation: it is about reporting sequelae to injury with an evidence-based foundation that meets a more stringent standard. Should that be accomplished, then even,- standard will be met or exceeded. According to the New York State Bar Association (n.d.). insurance law § 5104(a). (b). states tliat a person must have economic losses exceeding $50,000 or have one of the following: I^H Death Dismemberment , ^_ Significant disfigureme • Fracture "• Loss of a fetus Permanent loss of use of a body organ, member, function, or system Permanent consequential limitation of a body'or or member Significant limitation of use of a body function or system Medically determined injury or impairment of a noifl permanent nature which prevents the injured person from performing substantially all of the material acts which constitute such person's usual and customary daily activities for not less than 90 days during the 180 days immediately following the occurrence of the injury or impairment. ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^_ The New York State Bar Association (n.d.) also reports: ' In order to establish a permanent consequential limitation or a significant limitation of use. the medical evidence submitted by plaintiff must contain objective, quantitative evidence with respect to diminished range of motion or a qualitative assessment comparing plaintiffs present limitations to the nonnal function, purpose and use of the affected body organ, member, function or system." Tourc v. Avis Rcnt-A-Car Systems. 98 N.Y.2d 345. 353. 746 N.YS.2d 865 (2002). The Court of Ap- peals in Toure v. Avis Rcnt-A-Car Systems established that an expert's conclusory findings, without support, will not suffice to establish a serious injury under the Insurance Law. Sec also. Sarkis v. Gandy. 15 A~D.3d 942. 789 N.Y.S.2d 578 (4 Dept. 2005) (holding that plaintiff did not sustain a serious injury where plaintiffs experts made only conclusory. unsupported findings with respect to range of motion): Simpson v. Fey rer. 27 A.D.3d 881. 811 N.Y.S.2d 788 (3 Dcpt. 2006): Hock v.'Avilcs, 21 A.D.3d 786. 801 N.Y.S.2d 572 (1 Dcpt. 2005). In quantifying the limitations of use a plaintiff lias incurred, he/she is required to show more than a ' mild, minor or slight limitation of use." Miki v. Shufclt. 285 A.D.2d 949. 728 N.Y.S.2d 816 (3 Dcpt. 2001). In Miki v. Shufclt. the court held that the plaintiff failed to establish either a permanent consequential limitation of use ora significant limitation of use where the plaintiffs own experts characterized the disability as "mild." Further, the court stated that findings of limited range of motion failed to establish a serious injury where the medical experts provided no details as to these findings and failed to show how they were ascertained. See also. Brandt-Miller v. McArdlc. 21 A.D.3d 1152. 801 N.Y.S.2d 834 (3 Dcpt. 2005). Proof of a hcrniated disc, without additional objective medical evidence establishing tliat the accident resulted in significant physical limitations, is not alone sufficient to establish a serious injury. Pommells v. Perez, 4 N.Y.3d 566.574.797 N.Y.S.2d 380 (2005): Kcarsc v. New York City Transit Authority. 16 A.D.3d 45. 789 N.Y.S.2d 281 (2 Dept. 2005); John v. Engel, 2 A.D.3d 1027. 768 N.Y.S.2d 527 (3 Dept. 2003). In John v. Engcl. the court held that even though plaintiffs MRI showed a herniatcd disc at C5-6. plaintiffs injury did not constitute a serious injury because the plaintiffs medical records revealed no evidence of objective tests to determine any loss of range of motion or spasm or muscle weakness or tingling sensations. Sec also. Grimes-Carrion v. Carroll. 17 A.D.3d 296. 794 N.YS.2d 30 (1 Dcpt. 2005) (holding that plaintiff did not establish a serious injury under cither the permanent consequential limitation qualifier or the significant limitation qualifier where expert did not quantify spinal range of motion limitations until over 3 years after the accident); but sec. Dcsulmc v. Stanya. 12 A.D.3d 557. 785 N.Y.S.2d 477 (2 Dcpt. 2004) (holding that quantified limitations of range of motion established a serious injury). Plaintiffs subjective complaints of pain, without any objective medical evidence in support, arc insufficient to establish a serious injury. Gonzalez v. Green. 24 A.D.3d939.805N.Y.S.2d 450 (3 Dcpt. 2005) citing. Schcerv. Kou-beck. 70 N.Y.2d 678. 679. 518 N.Y.S.2d 788 (1987) (holding that pain alone cannot establish a basis for a serious injury). (http://www.nysba.org/workarca/Down-loadAssct.aspx?id=28534) The standard set by the courts in New York has clearly established that an experts findings must be compared to normal function and without objective, quantifiable support, or there will not be sufficient evidence to establish serious injury. When utilizing ranges of motion to quantify functional losses, there must be more than a "mild, moderate, or slight" loss. In addition, the courts in New York have held that bodily injury without evidence of significant physical limitation is not enough to establish serious bodily injury. Pain alone without any supportive, objective medical evidence is insufficient to establish serious injury. Although this standard exists in New York, main other states do not adhere to that standard with a caveat. Having lectured to and educated more than 100.000 lawyers in 30 states, and in return having received counsel from them, main have reported that if New York"s standard was being adhered to and documented accordingly, all of these lawyers" clients would have a much easier time being awarded fair and equitable settlements and verdicts. New York's standard also fits into the Colossus algorithms, again, if the functional losses and other required clinical findings (Colossus drivers) arc documented properly. Based on court rulings nationwide, range of motion is one inexpensive and accepted method of objectively documenting functional losses. The defense, however, often contends that the test is "mostly subjective." thereby putting the burden of subjectivity on the treating doctor. The American Medical Association's (AMA) Guides to the Evaluation of Permanent Impairment. Sixth Edition (2008) states that, "range of motion may be used to monitor clinical progress in individuals." (p. 558). while the fifth edition sets forth the accepted standard for objectively determining ranges of motion. Acquiring the ranges, according to the Guides to the Evaluation of Permanent Impairment. Fifth Edition (2001). "Because the small joints of the spine do not lend themselves readily to two-arm goniomctric measurements and measuring a spines segment's mobility is confounded by motion above and below the assessed points, an inclinometer is the preferred device for obtaining accurate, reproducible measurements in simple, practical and inexpensive way. The subcutaneous bony stnictures that mark the upper and lower ends of the three spine regions can be palpated readily" (p. 400). The AMA's fifth edition of Guides offers numerous examples of inclinometers, and in even example, they utilize a two-piece inclinometer. Many doctors erroneously utilize either an arthrodial protractor or goniometer for spinal ranges of motion. A goniometer is expressly utilized for extremities, while an arthrodial protractor has no degree of reproducible reliability, and. therefore, the AMA's Guides recommends using the two-piece inclinometer with the following methodology: TeasT fliree Tneasurel ments in the same region J 2. Calculate the average of three indi\ idual tests of the same region 13. Each set must fall within 5 to 10°/d of each other using the highea number I 4. If you cannot get three measurements within 5 to 10%. repeat the test up to six times (American Medical Association, 2001, p. 403) It is within the accepted standard to use cither manual or mechanical inclinometers with the suggestion that you calibrate the instrument on a monthh basis. When testifying for a patient having used an electronic inclinometer, you are often asked about the last time the instrument was calibrated. As a result and as a matter of practicing from a posture of clinical excellence, it is suggested tliat you calibrate all of your instruments on a monthh basis for both clinical accuracy and medical-legal reasons. In addition, according to Mayer. Kondraskc. Bcals. and Gatchcl (1997). "Spinal sagittal motion measurements may be performed accurately using computerized inclinomctry. Device error was negligible in this study and was usually a small factor compared with error associated with the test procedures. Test administrator training deficiencies were the major source of error in this study and probably contributed similarly to mcthodologic problems in the scientific literature critical of human performance tests using challenging protocols" (p. 1983). Therefore, training is a critical component in acquiring an accurate measurement, and once accomplished, the scientific literature bears evidence to the accuracy of the examination in a calibrated instrument. As a result of utilizing a two-part inclinometer, you can now report loss of function utilizing range of motion in degrees by using the State of New York's stringent standard of loss of function. You can also do that with a great degree of medical certainty by adhering to the industry standard, the AMA's Guides, of objectively certifying that loss of function. At the core, these standards allow us to practice from a posture of clinical excellence and render a higher level of certainty in concluding diagnoses, prognoses, and treatment plans for all of our patients. Dr. Mark Studin is an adjunct assistant professor in clinical sciences at the University Of Bridgeport College OfCliiropractic and a clinical presenter for the Slate ofXew York at Buffalo, School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences for postdoctoral education, teaching MRI spine interpretation and Iriaging trauma cases. He is also the president of the Academy of Chiropractic leaching doctors of chiropractic how to interface with the legal community (www. DoclorsPIProgram.com). teaches MRI interpretation and triaging trauma cases to doctors of all disciplines nationally, and studies trends in health care on a national scale (www.TeachDoctors.com). He can be reached at DrMark'iiAcademyoJChi-ropractic.com or at 631-786-4253. References: 1. AVir York Stale Bar Association, (n.d.) Serious injury threshold. Retrieved on August 4, 2014 from http: www.nvsba.org workarea DownloadAsset.aspx? id- 28534 2. Rondinelli, R. D. (Ed). (2008). Guides to Ihe evaluation ofpermaneni impairment. Sixth edition. United States of America: American \ ledical Association. 3. Cocchiarella, L., & Anderson. G. B. (Eds.). (2001). Guides to the evaluation of permanent impairmenl. Fifth edition. United States of America: American Medical Association. 4. Mayer, T. G., Kondraske, G., Beats, S. B., & Galchel, R. ./. (1997). Spinal range of motion: Accuracy and sources of error with inclinomelric measurement. Spine, 22(17), 1976-1984.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue