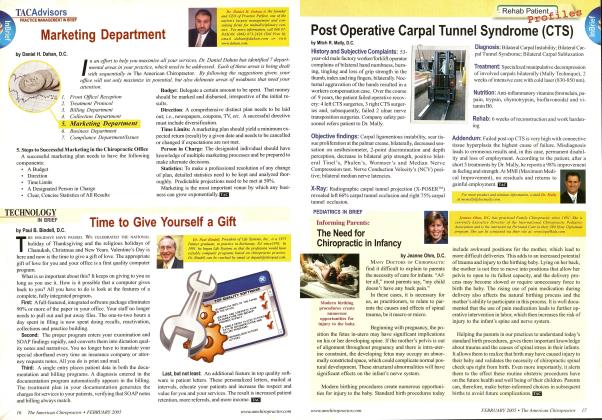

History The young patient fell on an outstretched arm while playing football. Discussion The "S" shape and normal overlap with the upper ribcage renders the clavicle a difficult structure to evaluate on straight anteroposterior projections. The most optimum view is anteroposterior projections with 15 degrees cephalad tube an-gulation. Weights (10-15 pounds) may be held to aid in detecting undisplaced fractures. The exposure factors should be approximately half of that utilized in standard shoulder projections, to prevent overexposure. Radiological Features Generally, a clavicle fracture follows direct trauma and is the most common bone fractured during birth and in childhood. Medial Clavicle Fractures This is the least common site, representing only approximately 5% of all clavicle fractures.1 These are difficult to observe and usually require CT scans. Middle Clavicle Fractures This is the most common site, representing approximately 80% of all clavicle fractures.1 A force applied to the distal end of the "S" shaped clavicle creates a shearing effect at the middle third, producing the fracture. The fracture is usually complete, with the medial fragment elevated by the action of the sternocleido-mastoid muscle, and the lateral fragment depressed by the weight of the shoulder and upper extremity. In addition to mis- alignment, an overlap at the fracture site is common, with the distal fragment usually lying below the medial fragment. Healing is often associated with extensive callus formation. Lateral Clavicle Fractures These account for approximately 15% of all clavicle fractures.' There are three varieties: undisplaced; displaced, where the distal fragment moves anterior and inferior; and 3) articular surface extension. Whenever a fracture of the lateral third is identified, weight bearing stress views should be obtained to clarify the status of the coracoclavicular ligaments.2 Notably, fractures that extend into the joint frequently precipitate the onset of degenerative arthritis. Complications of Clavicle Injuries Childhood clavicular fractures usually heal without sequelae; however, in adults, the incidence of complications increases. Neurovascular Damage. Associated injury to the underlying neurovascular structures most frequently involves the subclavian artery, less commonly the vein and, occasionally, the bra-chial plexus and sympathetic chain.' Com-pressive effects from the hypertrophic callus can also precipitate pressure-related neurovascular disturbances.1-4 Nonunion A failure to unite the fracture requires surgical fixation. The key signs of nonunion are located at the fracture margins, where sclerosis, rounding, and a smooth contour will be visible. Malunion In the presence of fragment overlap and massive callus formation, a cosmetic deformity may result. Correction requires osteotomy, realignment and fixation. Degenerative Arthritis Painful degenerative arthritis frequently follows intra-articular fractures of the clavicle. This is evidenced by loss of joint space, sclerosis and osteophyte formation. Post-Traumatic Osteolysis A peculiar bone response to clavicular injury is resorption of the distal segment, usually 1 -3 mm, but never more than 2-3 cm. The initiating injury may be relatively minor, often lacking the severity of that required to cause a fracture or dislocation. It first becomes radiologically visible 2-3 months after injury. The precise mechanism is uncertain, although syn-ovial hypertrophy suggests inflammatory osteoclastic activity.5 Pain is mild to moderate, while the disorder takes a self-limiting course over a number of months. The earliest radiographic sign in the development of osteolysis is a cystic rarefaction of the clavicular subarticular cortex, followed by cortical dissolution.5-6 The joint appears wide and the clavicular surface is frayed and irregular or cup-shaped. With healing, there are varying degrees of bony reconstitution to complete restoration of structure to a permanently tapered distal clavicle and increased joint space. ► See pg 61 for References M Dr. Terry R. Yovhutn is a second-generation chiropractor ami a cum iaude graduate of the National College of Chiropractic, where he subsequently completed his radiology specialty. He is currently Director of the Rocky Mountain Chiropractic Radiological Center, in Denver. CO. an Adjunct Professor of Radiology at the Los Angeles College of Chiropractic. as well as an instructor of Skeletal Radiology at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, Denver. CO. Dr. Yochum is, also, a consultant fo Health Care Mamtfac- luring Company that offers a Stored Energy xvstctn. For more information. Dr. Yochum can he reached at: 103-940-9400 or In e-mtiil at [email protected]. Dr. Child Mania is a 1999 Ma-gna Cum Laude graduate of National College ql Chiropractic. ► Figure 1. Note the complete fracture of the midshaft of the clavicle

View Full Issue

View Full Issue