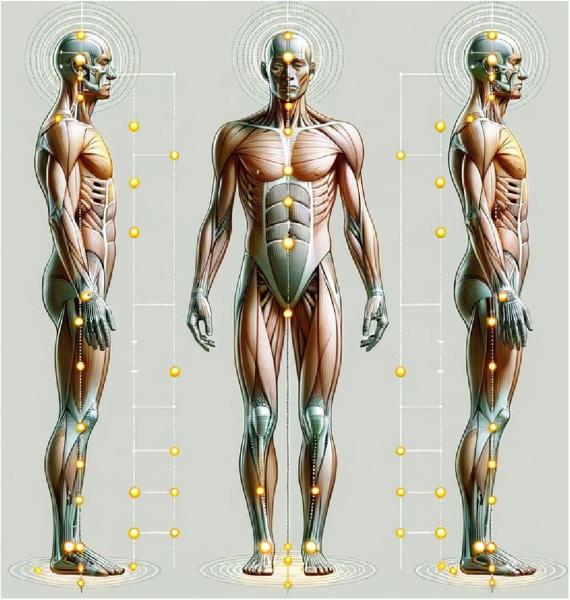

THE HUMAN BODY FUNCTIONS as an integrated system where motion and stability at one joint affect every other joint in the chain. Understanding this interconnectedness — the kinetic chain —provides a crucial framework for addressing musculoskeletal dysfunction and optimizing patient outcomes.

The kinetic chain represents the interconnected network of joints, muscles, and neural pathways that transmit forces throughout the body. Each segment affects those above and below it, creating a dynamic relationship between seemingly distant structures.1 This chain extends from the feet through the ankles, knees, hips, and spine, terminating at the cranium.

Recent research has expanded our understanding beyond traditional joint-focused approaches to include fascial connections. Dr. Lindsay’s “Integrated Kinetic Chain Model” demonstrates how myofascial continuities transmit forces throughout the body, often explaining why symptoms appear distant from their actual source.2 This integrated perspective helps explain why dysfunction in the foot can manifest as pain in the low back or even the neck.

Maintaining optimal kinetic chain function depends on three critical factors: skeletal structure, soft tissue integrity, and neurological control. Charrette notes, “Posture is determined in part by the shape and size of the underlying bone structure, as well as the alignment of the joints.”3 When any component of this system fails, compensatory patterns emerge that can lead to pain and dysfunction anywhere within the chain.

The foot serves as the foundation of the kinetic chain, with its three critical arches — medial longitudinal, lateral longitudinal, and anterior transverse — providing essential support and shock absorption. When properly supported, these arches create a stable base that optimizes force transmission through the kinetic chain.4

Each arch serves a specific biomechanical purpose:

1. Medial longitudinal arch: Provides primary shock absorption during gait and prevents excessive pronation.

2. Lateral longitudinal arch: Stabilizes the lateral foot during weight transfer.

3. Anterior transverse arch: Distributes pressure across the metatarsal heads and prevents forefoot splaying.

Research by Huang et al. confirms that the integrity of these arches depends primarily on ligamentous support rather than muscular activity.5 The plantar fascia and spring ligament provide up to 80% of arch support, with muscles contributing secondarily. This explains why orthotics supporting all three arches have demonstrated significant efficacy in reducing foot and low back pain.6

Pronation is a normal triplanar motion involving calcaneal eversion, talar adduction, and plantar flexion. However, when excessive or prolonged, pronation disrupts the entire kinetic chain through predictable biomechanical compensations.

During excessive pronation, the following biomechanical events occur in sequence:

1. The medial arch collapses, allowing the navicular to drop inferiorly and medially.

2. The talus adducts and plantar flexes, forcing internal rotation of the tibia.

3. Tibial internal rotation drives femoral internal rotation.

4. Femoral rotation alters hip biomechanics, typically limiting external rotation.

5. Pelvic alignment changes to accommodate lower extremity rotation.

6. Compensatory spinal curves develop to maintain eye level with the horizon.7

This cascade explains the clinical observation that “everything changes when the foot hits the ground.”8 The forces generated at heel strike — 2.5 times body weight during walking and 3.5 times during running — transmit shock waves that can be measured at the cranium within milliseconds.9

“The kinetic chain represents a fundamental paradigm for understanding how the body functions as an integrated system.”

Beyond biomechanical effects, pronation significantly impacts proprioception and neurological function. The foot contains an extraordinary concentration of mechanoreceptors that provide critical sensory input for balance and posture. When pronation alters standard joint mechanics, it disrupts this proprioceptive feedback system.10

This neurological disruption creates what Kent describes as “dysafferentation,” or an imbalance in sensory input where mechanoreceptor activity decreases while nociceptor firing increases.11 This shift activates the sympathetic nervous system and contributes to central sensitization, explaining why foot dysfunction can lead to widespread symptoms.

Understanding the kinetic chain’s integrated nature informs a comprehensive approach to patient care:

A thorough kinetic chain assessment must evaluate:

1. Static posture from multiple planes.

2. Dynamic movement patterns during functional activities.

3. Joint-specific motion restrictions.

4. Neurological responsiveness, including proprioception.

Treatment Approach

Effective intervention requires addressing all components of the kinetic chain:

1. Joint mobilization: Specific adjustments to restore optimal mobility at restricted segments.

2. Three-arch support: Custom orthotics that stabilize all three arches prevent recurrence by addressing the foundation.

3. Neuromuscular reeducation: Targeted exercises to improve proprioception and motor control.

4. Fascial release: Techniques addressing myofascial continuities that may transmit tension through the system.

Research demonstrates that this integrated approach produces superior outcomes. A 2017 randomized controlled trial published in the Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation found that custom three-arch orthotics reduced low back pain by 34.5% and improved function by 32.3% when paired with spinal adjustments.12

The kinetic chain represents a fundamental paradigm for understanding how the body functions as an integrated system. From the three-arch foundation of the foot to the complex movements of the spine, each component influences all others through biomechanical and neurological connections.

Pronation serves as a critical link in this chain, with excessive motion creating predictable compensatory patterns that can manifest as pain and dysfunction throughout the body. By recognizing these relationships and implementing comprehensive interventions that address both structural and neurological components, clinicians can provide more effective care that resolves the underlying causes rather than merely treating symptoms.

The evidence demonstrates that supporting all three arches of the foot while addressing specific joint restrictions throughout the kinetic chain produces superior outcomes for patients with musculoskeletal complaints. This integrated approach represents the future of chiropractic care — one that recognizes that the body truly functions as an interconnected whole.

Dr. Mark Charette is a 1980 summa cum laude graduate of Palmer College of Chiropractic and a former All-American swimmer. He is a frequent guest speaker at chiropractic colleges and has taught over 2,200 seminars worldwide on extremity adjusting, biomechanics, and spinal adjusting techniques. He has authored a book on extremity adjusting and produced an instructional video series. His lively seminars emphasize a practical, hands-on approach. As a Foot Levelers Speakers Bureau member, he travels the country sharing his knowledge and insights. Learn more at www.FootLevelers.com/more.

1. Charrette MN. How to Hone Your Expertise in Postural Assessment. Professional journal citation, 2023.

2. Lindsay D. Integrated Kinetic Chain Model. University of Calgary research publication, 2023.

3. Charrette MN. Postural faults can arise from injury, illness, habit, or variations in neuromuscular reflexes. Professional journal citation, 2024.

4. Botte RR. An interpretation of the pronation syndrome and foot types of patients with low back pain. J Am Podiatry Assoc. 1981 May;71(5):243-53. doi: 10.7547/87507315-71-5-243. PMID: 6453891.

5. Huang CK, Kitaoka HB, An KN, Chao EY. Biomechanical evaluation of longitudinal arch stability. Foot Ankle. 1993 Jul-Aug;14(6):353-7. doi: 10.1177/107110079301400609. PMID: 8406252.

6. Basmajian JV, Stecko G. The role of muscles in arch support of the foot. J Bone Joint SurgAm. 1963 Sep;45:1184-90. PMID: 14077983.

7. Rothbart BA, Estabrook L. Excessive pronation: a major biomechanical determinant in the development of chondromalacia and pelvic lists. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1988 Oct; 11 (5): 373-9. PMID: 2976805.

8. Charrette MN. When the Foot Hits the Ground, Everything Changes. Pro fessional journal citation, 2021.

9. Light LH, McLellan GE, Klenerman L. Skeletal transients on heel strike in normal walking with different footwear. J Biomech. 1980;13(6):477-80. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(80)90340-1. PMID: 6447153.

10. Freeman MA, Wyke B. Articular contributions to limb muscle reflexes. The effects of partial neurectomy of the knee-joint on postural reflexes. Br J Surg. 1966 Jan;53(l):61-8. doi: 10.1002/bjs.l800530116. PMID: 5901916.

11. Kent C. A four-dimensional model of vertebral subluxation [Internet]. Huntington Beach, CA: Dynamic Chiropractic. 2011. Available from: https://dynamicchiropractic.co...

12. Cambron JA, Dexheimer JM, Duarte M, Freels S. Shoe orthotics for the treatment of chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2017 Sep;98(9): 1752-1762. doi: 10.1016/j. apmr. 2017.03.028. Epub 2017 Apr 30. PMID: 28465224.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue